Free download.

Book file PDF easily for everyone and every device.

You can download and read online The Bible, Douay-Rheims, Book 15: 1 Esdras The Challoner Revision file PDF Book only if you are registered here.

And also you can download or read online all Book PDF file that related with The Bible, Douay-Rheims, Book 15: 1 Esdras The Challoner Revision book.

Happy reading The Bible, Douay-Rheims, Book 15: 1 Esdras The Challoner Revision Bookeveryone.

Download file Free Book PDF The Bible, Douay-Rheims, Book 15: 1 Esdras The Challoner Revision at Complete PDF Library.

This Book have some digital formats such us :paperbook, ebook, kindle, epub, fb2 and another formats.

Here is The CompletePDF Book Library.

It's free to register here to get Book file PDF The Bible, Douay-Rheims, Book 15: 1 Esdras The Challoner Revision Pocket Guide.

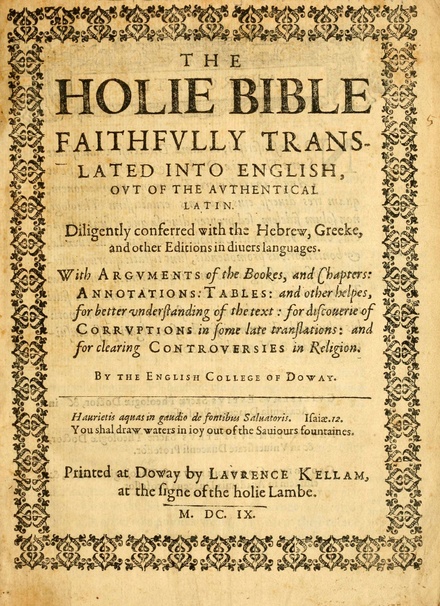

The Bible, Douay-Rheims, Book 1 Esdras The Challoner Revision THE HOLY BIBLE Translated from the Latin Vulgate Diligently Compared with the.

Table of contents

Although the Douay Old Testament did not appear until , it was translated decades earlier, but the Rhemists lacked the funds to have it printed. Gregory Martin died in , probably from the excess of work he did on the translation in the preceding decade. It has been a source of conjecture and wonder as to which Vulgate the Rhemists primarily Gregory Martin did use, as it was an extremely good edition, and is in virtually perfect agreement with the later Clementine edition of the Vulgate.

The Notes from this edition were memorialized in the many later editions of the Haydock Bible. In Dr. Kenrick, Archbishop of Baltimore, began translating the Vulgate N. It was while he was making this translation that John Henry Newman was approached by Cardinal Wiseman to re-translate the Vulgate. When Kenrick got wind of this, there was such a stir made, that the project for Newman translating the Bible was dropped.

One can certainly wonder at how differently English Catholic history might have unfolded had Kenrick not prevented Newman from translating the Bible anew.

Buy It Now

Thanks for the info on the Douay-Rheims source text. I should have known taken the Rheims was published in and the Clementine in Also, I refrained from mentioning the more obscure translations and various editions of the DR and Clementine Vulgate cause I tried sticking to the more popular ones people would recognize.

Douay-Rheims Bible Apologetics. Sacred Scripture. NHInsider September 23, , pm 2. Omyo12 September 23, , pm 5. Example: Hebrews 1 Rheims 1 Diversely and many ways in times past God speaking to the fathers in the prophets, 2 last of all in these days hath spoken to us in his Son, whom he hath appointed heir of all, by whom he made also the worlds. For the English speaking world, the Douay Rheims was the only Catholic Bible from revised in until when the Rheims was revised again from the Latin and called the Confraternity New Testament some of the Old Testament was also revised The Confraternity project was stopped when Pope Pius XII declared in the encyclical Divino Afflante Spiritu that the Bible would be translated from the original tongues of Hebrew and Greek and no longer from the Latin.

The New American Bible was finished in NHInsider September 24, , am 7. Well, yes and no. Omyo12 September 24, , am 8. It was slightly revised in and again in In , the American Standard Version was revised by a very conservative group of scholars called the Lockman Foundation and published the Amplified Bible. NHInsider September 24, , am 9. Omyo12 September 24, , am NHInsider September 24, , am InnocentSmith September 24, , pm Rheims New Testament. NHInsider September 25, , am The Rheims is the NT.

The Holy Bible

The Douay is the OT. Omyo12 September 25, , pm This Bible became known as the Latin Vulgate — These original manuscripts are now lost — However, there is a critical edition in an attempt to reconstruct them: Weber-Gyrson Biblia Sacra Vulgata Manuscript to consider: Codex Amiatinus commissioned in AD At the Council of Trent , in response to the Reformation, the canon was made official and the Latin Vulgate was declared authoritative.

AmbroseSJ September 26, , am Diligently conferred with the Hebrew, Greek and other Editions". The cause of the delay was "our poor state of banishment", but there was also the matter of reconciling the Latin to the other editions. William Allen went to Rome and worked, with others, on the revision of the Vulgate.

- Who Rescued Who?: Paws That Refreshed!

- The Farmer of Inglewood Forest; Or, an Affecting Portrait of Virtue and Vice?

- Poems of Love, Romance and Heartbreak 1981 - 2014.

- Hero in My Own Eyes: Tripping a Life Fantastic.

- Shop by category;

- Customers also bought...;

- Related Tags!

The Sixtine Vulgate edition was published in The definitive Clementine text followed in Worthington, responsible for many of the annotations for the and volumes, states in the preface: "we have again conferred this English translation and conformed it to the most perfect Latin Edition. Genesis iii, 15 does not reflect either Vulgate. The Vulgate was largely created due to the efforts of Saint Jerome — , whose translation was declared to be the authentic Latin version of the Bible by the Council of Trent.

While the Catholic scholars "conferred" with the Hebrew and Greek originals, as well as with "other editions in diverse languages", [7] their avowed purpose was to translate after a strongly literal manner from the Latin Vulgate, for reasons of accuracy as stated in their Preface and which tended to produce, in places, stilted syntax and Latinisms. The following short passage Ephesians —12 , is a fair example, admittedly without updating the spelling conventions then in use:. The Gentiles to be coheires and concorporat and comparticipant of his promise in Christ JESUS by the Gospel: whereof I am made a minister according to the gift of the grace of God, which is given me according to the operation of his power.

To me the least of al the sainctes is given this grace, among the Gentils to evangelize the unsearcheable riches of Christ, and to illuminate al men what is the dispensation of the sacrament hidden from worldes in God, who created all things: that the manifold wisdom of God, may be notified to the Princes and Potestats in the celestials by the Church, according to the prefinition of worldes, which he made in Christ JESUS our Lord. In whom we have affiance and accesse in confidence, by the faith of him.

Other than when rendering the particular readings of the Vulgate Latin, the English wording of the Rheims New Testament follows more or less closely the Protestant version first produced by William Tyndale in , an important source for the Rheims translators having been identified as that of the revision of Tyndale found in an English and Latin diglot New Testament, published by Miles Coverdale in Paris in Consequently, the Rheims New Testament is much less of a new version, and owes rather more to the original languages, than the translators admit in their preface.

Where the Rheims translators depart from the Coverdale text, they frequently adopt readings found in the Protestant Geneva Bible [11] or those of the Wycliffe Bible, as this latter version had been translated from the Vulgate, and had been widely used by English Catholic churchmen unaware of its Lollard origins. Nevertheless, it was a translation of a translation of the Bible. Many highly regarded translations of the Bible routinely consult Vulgate readings, especially in certain difficult Old Testament passages; but nearly all modern Bible versions, Protestant and Catholic, go directly to original-language Hebrew, Aramaic , and Greek biblical texts as their translation base, and not to a secondary version like the Vulgate.

The translators justified their preference for the Vulgate in their Preface, pointing to accumulated corruptions within the original language manuscripts available in that era, and asserting that Jerome would have had access to better manuscripts in the original tongues that had not survived. In their decision consistently to apply Latinate language, rather than everyday English, to render religious terminology, the Rheims—Douay translators continued a tradition established by Thomas More and Stephen Gardiner in their criticisms of the biblical translations of William Tyndale.

Gardiner indeed had himself applied these principles in to produce a heavily revised version, which unfortunately has not survived, of Tyndale's translations of the Gospels of Luke and John. More and Gardiner had argued that Latin terms were more precise in meaning than their English equivalents, and consequently should be retained in Englished form to avoid ambiguity. However, David Norton observes that the Rheims—Douay version extends the principle much further.

In the preface to the Rheims New Testament the translators criticise the Geneva Bible for their policy of striving always for clear and unambiguous readings; the Rheims translators proposed rather a rendering of the English biblical text that is faithful to the Latin text, whether or not such a word-for-word translation results in hard to understand English, or transmits ambiguity from the Latin phrasings:. Hierom, that in other writings it is ynough to give in translation, sense for sense, but that in Scriptures, lest we misse the sense, we must keep the very wordes.

This adds to More and Gardiner the opposite argument, that previous versions in standard English had improperly imputed clear meanings for obscure passages in the Greek source text where the Latin Vulgate had often tended to rather render the Greek literally, even to the extent of generating improper Latin constructions. In effect, the Rheims translators argue that, where the source text is ambiguous or obscure, then a faithful English translation should also be ambiguous or obscure, with the options for understanding the text discussed in a marginal note:.

The translation was prepared with a definite polemical purpose in opposition to Protestant translations which also had polemical motives. Prior to the Douay-Rheims, the only printed English language Bibles available had been Protestant translations. The translators excluded the apocryphal Psalm , this unusual oversight given the otherwise "complete" nature of the book is explained in passing by the annotations to Psalm that "S. Augustin in the conclusion of his Sermons upon the Psalms, explicateth a mysterie in the number of an hundred and fieftie[.

In England the Protestant William Fulke unintentionally popularized the Rheims New Testament through his collation of the Rheims text and annotations in parallel columns alongside the Protestant Bishops' Bible. Fulke's original intention through his first combined edition of the Rheims New Testament with the so-called Bishop's Bible was to prove that the Catholic-inspired text was inferior to the Protestant-influenced Bishop's Bible, then the official Bible of the Church of England.

Douay - Rheims Bible - Challoner Revision - Catholic Gallery - Bible

Fulke's work was first published in ; and as a consequence the Rheims text and notes became easily available without fear of criminal sanctions. Not only did Douay-Rheims influence Catholics, but it also had a substantial influence on the later creation of the King James Version. The King James Version is distinguished from previous English Protestant versions by a greater tendency to employ Latinate vocabulary, and the translators were able to find many such terms for example: emulation Romans in the Rheims New Testament.

Consequently, a number of the Latinisms of the Douay—Rheims, through their use in the King James Version, have entered standard literary English. The translators of the Rheims appended a list of these unfamiliar words; [14] examples include "acquisition", "adulterate", "advent", "allegory", "verity", "calumniate", "character", "cooperate", "prescience", "resuscitate", "victim", and "evangelise". In addition the editors chose to transliterate rather than translate a number of technical Greek or Hebrew terms, such as " azymes " for unleavened bread, and "pasch" for Passover.

The original Douay—Rheims Bible was published during a time when Catholics were being persecuted in Britain and Ireland and possession of the Douay—Rheims Bible was a crime. By the time possession was not a crime the English of the Douay—Rheims Bible was a hundred years out-of-date. It was thus substantially "revised" between and by Richard Challoner , an English bishop , formally appointed to the deserted see of Debra Doberus.

- Arab Cinema Travels: Transnational Syria, Palestine, Dubai and Beyond (Cultural Histories of Cinema).

- Contributions to the Mineralogy of the Newark Group in Pennsylvania.

- BibleGateway.

Challoner's revisions borrowed heavily from the King James Version being a convert from Protestantism to Catholicism and thus familiar with its style. Challoner not only addressed the odd prose and much of the Latinisms, but produced a version which, while still called the Douay—Rheims, was little like it, notably removing most of the lengthy annotations and marginal notes of the original translators, the lectionary table of gospel and epistle readings for the Mass, and most notably the apocryphal books all of which save Psalm had been included in the original.

At the same time he aimed for improved readability and comprehensibility, rephrasing obscure and obsolete terms and constructions and, in the process, consistently removing ambiguities of meaning that the original Rheims—Douay version had intentionally striven to retain. The same passage of Ephesians —12 in Challoner's revision gives a hint of the thorough stylistic editing he did of the text:.

That the Gentiles should be fellow heirs and of the same body: and copartners of his promise in Christ Jesus, by the gospel, of which I am made a minister, according to the gift of the grace of God, which is given to me according to the operation of his power. To me, the least of all the saints, is given this grace, to preach among the Gentiles the unsearchable riches of Christ: and to enlighten all men, that they may see what is the dispensation of the mystery which hath been hidden from eternity in God who created all things: that the manifold wisdom of God may be made known to the principalities and powers in heavenly places through the church, according to the eternal purpose which he made in Christ Jesus our Lord: in whom we have boldness and access with confidence by the faith of him.

That the Gentiles should be fellow heirs, and of the same body, and partakers of his promise in Christ by the gospel: whereof I was made a minister, according to the gift of the grace of God given unto me by the effectual working of his power. Unto me, who am less than the least of all saints, is this grace given, that I should preach among the Gentiles the unsearchable riches of Christ; and to make all men see what is the fellowship of the mystery, which from the beginning of the world hath been hid in God, who created all things by Jesus Christ: to the intent that now unto the principalities and powers in heavenly places might be known by the church the manifold wisdom of God, according to the eternal purpose which he purposed in Christ Jesus our Lord: in whom we have boldness and access with confidence by the faith of him.

That the gentiles should be inheritors also, and of the same body, and partakers of his promise that is in Christ, by the means of the gospel, whereof I am made a minister, by the gift of the grace of God given unto me, through the working of his power. Unto me the least of all saints is this grace given, that I should preach among the gentiles the unsearchable riches of Christ, and to make all men see what the fellowship of the mystery is which from the beginning of the world hath been hid in God which made all things through Jesus Christ, to the intent, that now unto the rulers and powers in heaven might be known by the congregation the manifold wisdom of God, according to that eternal purpose, which he purposed in Christ Jesu our Lord, by whom we are bold to draw near in that trust, which we have by faith on him.

Challoner issued a New Testament edition in He followed this with an edition of the whole bible in , making some further changes to the New Testament. He issued a further version of the New Testament in , which differed in about 2, readings from the edition, and which remained the base text for further editions of the bible in Challoner's lifetime. Gone also was the longer paragraph formatting of the text; instead, the text was broken up so that each verse was its own paragraph. The three apocrypha , which had been placed in an appendix to the second volume of the Old Testament, were dropped.

Challoner's New Testament was extensively further revised by Bernard MacMahon in a series of Dublin editions from to , for the most part adjusting the text away from agreement with that of the King James Version, and these various Dublin versions are the source of many, but not all, Challoner versions printed in the United States in the 19th century.

Editions of the Challoner Bible printed in England sometimes follow one or another of the revised Dublin New Testament texts, but more often tend to follow Challoner's earlier editions of and as do most 20th-century printings, and on-line versions of the Douay—Rheims bible circulating on the internet. Husenbeth in was approved by Bishop Wareing. A reprint of an approved edition with Haydock's unabridged notes was published in by Loreto Publications. Martin's texts. This revision became the 'de facto' standard text for English speaking Catholics until the twentieth century.

It is still highly regarded by many for its style, although it is now rarely used for liturgical purposes. The notes included in this electronic edition are generally attributed to Bishop Challoner. Yazar: Zhingoora Bible Series.